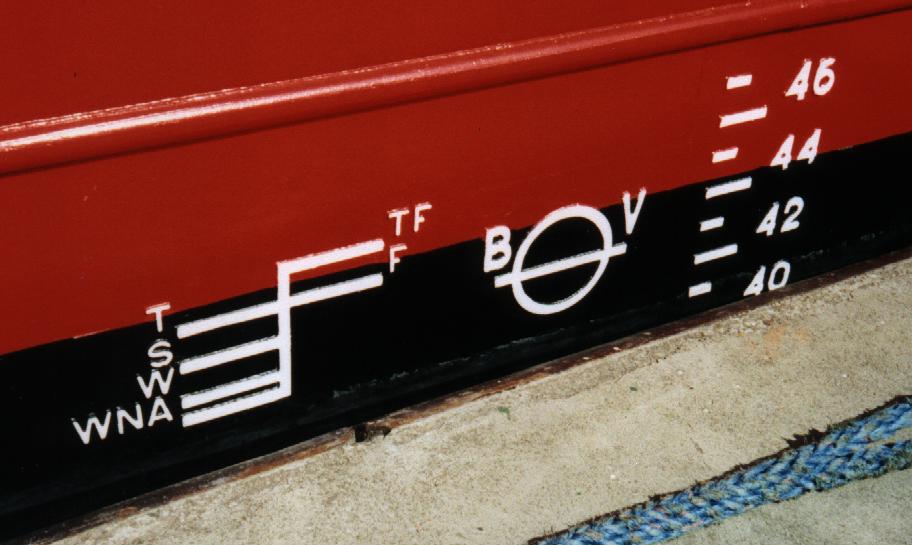

If you look at pretty much any cargo vessel, you’ll see the front of it has a bunch of stripes painted on it, often with a circle with a line through it on one of them. This is a Plimsoll line, or a lading line, or a Plimsoll mark. The original Plimsoll mark is that barred circle, which was what Plimsoll himself advocated for, after a lot, a lot of people died in overloaded colliers (coal carrying ships). There wasn’t really a disincentive for ship owners for overloading. Either the cargo arrived, and you got paid, or the ship sank, and you got the insurance. This big circle existed so that any sailor could look for it and see it and decide whether to get on that particular ship or not. [1]

The lines mark how much freeboard the ship needs in different water conditions. Freeboard is how much of the ship is sticking out of the water. For example, salt water is more buoyant than freshwater, so you have more margin for error with fresh water, because your load is less heavy. So you can pile on the coal (or containers) if you’re sailing around in a tropical freshwater lake or river. Warmer water is less dense than colder water, and also less stormy, so you similarly can put more stuff on the same ship if it’s in the tropics, or if it’s summer.

And then there is the bottom line. WNA means “Winter North Atlantic”. If we actually do end up putting cargo ships through the Northwest passage, we’ll probably use that line, too. I’d bet they use it rounding Cape Horn, too. It means “Do not load past this point. Rogue waves. Hurricanes. This ocean lives to fuck you up.”. If you’ve ever watched The Perfect Storm or Deadliest Catch, it’s that kind of weather. And in order to stay alive in that kind of weather, you need as much of your ship above water as is compatible with not going ass-over-teakettle. Mostly, once a ship is loaded, it’s loaded until you get where you’re going. (Unless your containers fall off, or you have a timber load that can be jettisoned, but those are edge cases (there’s different lading lines for timber-loaded ships))

Technology relevance

I would happily talk to you for another 500 words about this tiny pebble of history, but it’s something I’ve been thinking about as it relates to guardrails in technology. We put up fences on our roads because there’s a danger our vehicles will leave the place they’re supposed to be, which is bad for our safety and the safety of others. But there isn’t just one kind of guardrail. There’s the tensioned-wire kind between directions on the interstate, which are mostly designed to stop even trucks from crossing the center median. There’s metal-and-post, which are a compromise about getting to see the mountains without going off the cliff. There’s concrete barriers that protect construction workers. Each has their purpose, and their tradeoffs.

In an era where we have to assume that our data is being collected, and the data we collect, I think we need to get more nuanced about our guardrails. We need to think about what the worst possible outcome is, and then what the worst likely outcome is. We need to consider the dangers in different conditions, and whether our safety device may actually cause harm (I’m looking at you, age-verification laws). Maybe some data is lightweight and ephemeral and not likely to cause harm, like aggregated traffic counts. Some of it is very dangerous, like PII or biometrics. Some of it is medium until the circumstances change, and we build compromises around the way was it was in the beginning.

Guardrails are not the first line of defense in driving, and lading lines are not the only calculation made to ensure safe shipping. They’re just the obvious ways we have to say “this corner has a drop-off, this ocean is dangerous.”. In technology, we can’t really see what’s dangerous, and that means that some people feel like everything is safe, and some people feel like nothing is safe. Guidelines about how software is used and how information is stored will be helpful to all of us, so we can tell what’s worth being cautious about.

[1 Plimsoll was a weirdo, as many 19th century British dudes were, but he was quite literally a hero to the entire cargo-shipping community. People wrote actual songs about him. Triumphal parades, etc. And it wasn’t easy. He pretty much broke his health and his heart trying to push it through against the powers-that-were. If you’d like to read more about it, there’s a book called The Plimsoll Sensation, by Nicolette Jones]

UPDATE: Literally between me writing this and it posting, a YouTube channel called Oceanliner Designs made a 11-minute video with a much better explanation of displacement and lading: